Are North Carolina suburbs trending like national suburbs?

Published November 7, 2019

With the analysis settling on the 2019 odd-year elections, the national narrative appears to be focused on the suburban swings against the GOP and towards the Democrats. And in the 2019 general election in North Carolina's Ninth Congressional District, the 'swing' seemed to be more dichotomous in the 'suburbs.' More on that later.

First, an assumption: it is popularly imagined about the differences between 'urban' versus 'rural' areas of our nation and state. For example, an urban county contains a densely-populated central city (Mecklenburg County with Charlotte, Wake County with Raleigh), while 'rural' designates an area beyond a metropolitan area of the urban and surrounding suburbs, typically with low population density. Those are easily envisioned in their characteristics, and even more so nowadays in their 'political behavior.'

It's when you get into the 'suburbs' that popular conceptions of that type of region come into some potential differences. In my analyses, I rely on the U.S. Office of Management and Budget's 2017's classification of metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs. These MSAs designated a central city, surrounded by counties that are connected with the central city (surrounding suburban counties). Then, whatever counties are left, are considered 'rural' (and yes, there are micropolitan statistical areas, but I leave that for future analyses).

However, within the central city's urban county, there are 'suburban' areas within that urban county that may present a different perspective from the central city. For example, in Mecklenburg County, dominated by Charlotte, areas within Mecklenburg, such as Mint Hill, Pineville, Huntersville, and Davidson, among several, are considered Charlotte's 'suburbs.'

In applying these classifications to the Old North State's regions, I utilize a four category designation, especially when it comes to voter registration:

- voters who reside in the central city;

- voters who are inside the central city's urban county but outside the central city;

- the surrounding suburban counties; and then,

- the rural counties (those outside of the MSAs regions).

This page displays the different 'counties'--urban, suburban, and rural--in North Carolina.

Since we are a year out from the 2020 general election, I recently analyzed the November 2, 2019 voter registration data file of the 6.6 million active/inactive/temporary registered voters to look at how North Carolina voters are distributed among the four regions (listed above) and their party registrations.

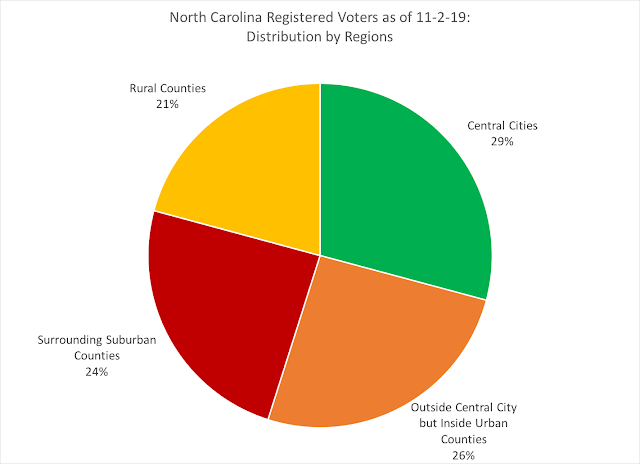

First, the distribution of NC's voters across the four regions show that one region dominates the state's voter pool.

Nearly thirty percent of NC's registered voters reside within a central city of the state, with another quarter being within the central city's county, making for 55 percent of NC voters in just 19 out of the state's 100 counties.

Another quarter of the voters reside in the 27 surrounding suburban counties, leaving barely two out of ten voters residing in state's rural counties.

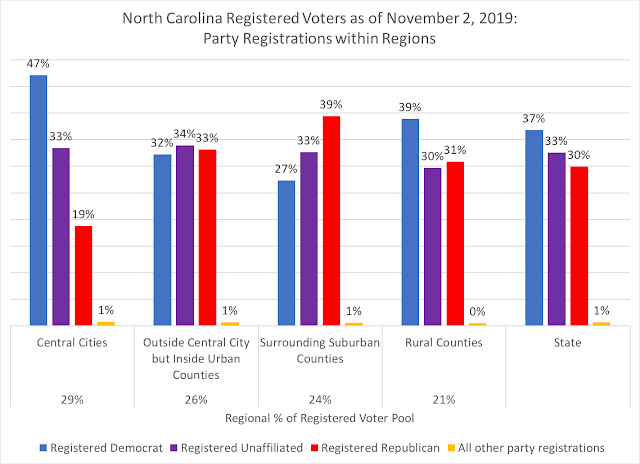

In terms of the party registration distribution for the state, the November 2nd data shows that registered Democrats are 37 percent of the state-wide pool, while registered unaffiliated voters are a third, and registered Republicans are 30 percent, with the remaining parties--Libertarian, Green, and Constitution--making up a combined one percent.

Among the four 'regions' as classified above, the party registration shows some distinct differences, as one has come to expect:

Within the central cities, registered Democrats are nearly half of the voters, with unaffiliated voters being a third, and registered Republican less than 20 percent. Moving into the urban county 'suburbs,' the party distribution is almost evenly divided among the three major registrations. It is once you move into the surrounding suburban counties where the Republican advantage is most acute, with nearly four of ten surrounding suburban voters registered GOP, while 27 percent are registered Democratic.

Finally, the rural registration is 39 percent Democratic, 30 percent unaffiliated, and 31 percent Republican, but that does not necessarily mean that Democrats dominate the rural counties of the state. That 39 percent registered Democrats are made up of older, white voters who are likely Republican voters, along with significant portions in the eastern portion of the state (along the Virginia and South Carolina state borders) of minority voters.

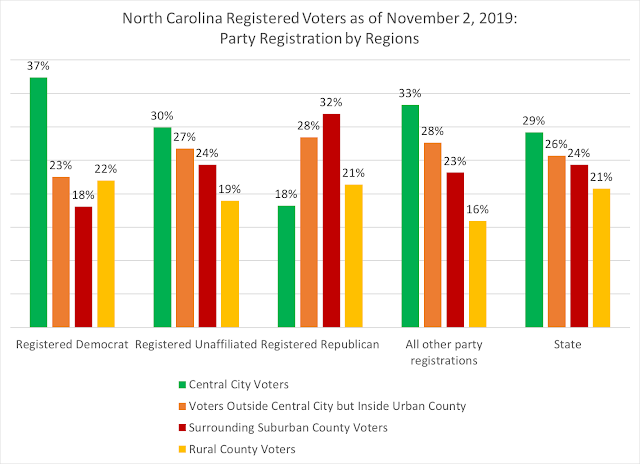

In flipping the data to present where the parties have their voters, this Democratic dominance in central cities is again rather unique among the three party registrations:

Nearly forty percent of registered Democrats in North Carolina reside in a central city, while only 18 percent are in surrounding suburban counties. Conversely, a plurality of registered Republicans (32 percent) reside in those surrounding suburban counties, while 18 percent are in the central cities. Among registered unaffiliated voters, their distribution mirrors the state's distribution.

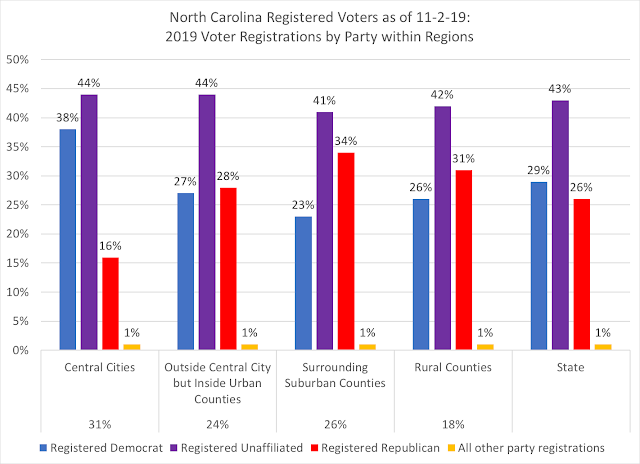

Finally, I looked at just this year's voter registration data (2019's new voters through October) to see how new voters were registering with the parties (or not) and where they were located.

Well over half (55 percent) of 2019's new voters are in urban counties, with 31 percent within the central cities and 24 percent outside of the city but still inside the county. Over a quarter of the new voters registered--26 percent--are in the surrounding suburban counties, and only 18 percent are in the rural counties.

Again, what is fascinating is how these voters in the different regions are deciding to register in terms of party affiliation. Statewide, this year's new voters are decidedly 'unaffiliated,' with 43 percent registering with neither major party. That figure is consistent across the four regions, in general, but the differences between registered Democrats and Republicans is markedly distinctive between central cities (where 38 percent registered Democratic to only 16 percent Republican) and surrounding suburban counties (where 34 percent registered Republican to 23 percent Democratic).

What this data tells me is that, in thinking about North Carolina as a battleground state next year, the easy configuration will be the "urban-rural" divide with the battlegrounds in the "suburbs." But this voter registration data tells us that there may be more nuances in how the two different 'suburbs' are politically.

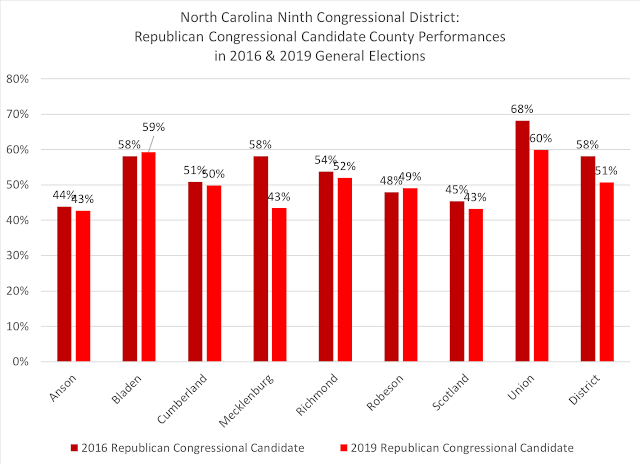

And we distinctly saw this in the recent 2019 Ninth Congressional District general election, especially if you compare two key counties against their 2016 electoral performances.

The current NC 9th stretches from urban Mecklenburg into suburban Union and down along the SC border into rural counties.

But the 'urban' areas of the Ninth include both the south part of Charlotte and the southeastern suburban areas such as Matthews and Mint Hill. And a 'shift' did occur in the NC 9th between the 2016 and 2019 general elections for Republican candidates:

If you look at how the 2019 Republican congressional candidate fared in Mecklenburg versus the 2016 performance (two different candidates, but both from Mecklenburg), it was a 15 point drop in support both inside and outside the central city in the urban county. In Union County, the surrounding suburban county, the drop was less, going from 68 percent down to 60 percent, and eight point drop. The remaining rural counties either saw slight drops or slight increases in GOP votes.

Taking this all into account, if the national narrative for 2020 is "the battle for the suburbs," as some are positing, and North Carolina is one of a handful of states that may decide the battle of the White House, Senate, House, gubernatorial and other contests next year, then the dichotomy between an 'urban-suburb' and 'surrounding suburb' may be an important distinction worth watching.