Renaming buildings at North Carolina colleges

Published July 23, 2020

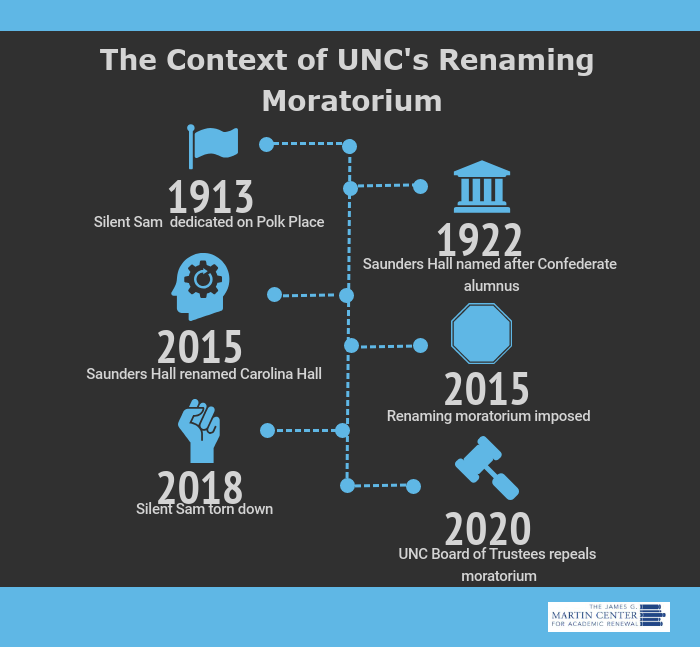

On June 17, the Board of Trustees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill voted to end the moratorium on renaming campus buildings associated with white supremacy or slavery.

An online petition sparked that change. Michael Rashaad Galloway, a recent alumnus, started the petition that gained over 9,500 signatures. Since the reversal, the Daily Tar Heel has released a list of about 30 buildings that were named after white supremacists to be considered for renaming.

Some buildings have already been renamed. In 2015, UNC changed Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall. William Saunders, a UNC graduate, fought in the Confederate Army and was a leader in North Carolina’s Ku Klux Klan. After the building was renamed, the Board of Trustees imposed a moratorium on any name changes for 16 years, until 2031.

Three years later, a group of local and student protesters tore down “Silent Sam,” a statue of a Confederate soldier erected in 1913, from his pedestal. The university still does not have a plan for what to do with the statue, erected 50 years after the Civil War (like many other Confederate monuments across the Jim Crow South).

In lifting the moratorium, chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz stated, “we live in a world where change should be fueled by a desire to create and embrace a more inclusive world, not resisted by fear.” Guskiewicz clearly supports the university’s shift toward inclusivity, but the standards for how to “reconcile our past,” as he said, remain unclear.

Like UNC, universities across the country are considering renaming or removing controversial memorials. As statues are toppled—from Confederate monuments to statues of George Washington and abolitionists—the criteria for what stays and what goes has been dictated by impassioned people without a central guidance for what change should look like.

There is a need for a systematic process to review monuments with alleged connections to white supremacy or slavery. Without a set standard, though, a slippery slope is created that leaves no name safe. For example, some question whether the monuments of George Washington or Abraham Lincoln should be removed because each has a negative connection to slavery. Washington owned slaves and Lincoln didn’t issue the Emancipation Proclamation until halfway through the Civil War.

The standard for keeping or defending monuments is an ongoing debate. National Geographic and NPR have also covered the issue, and UNC is not alone in struggling to find a standard to follow without seeing its entire history as suspect and condemned.

Kathryn Goodwin is a Martin Center intern and a junior studying political science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.