- The North Carolina Supreme Court correctly decided that partisan gerrymandering claims are “nonjusticiable, political questions”

- The General Assembly should avoid using partisan data when it redraws maps later this year

- Now is a good time to consider redistricting reform

While the North Carolina Supreme Court correctly affirmed that questions of partisanship in redistricting are out of its purview, the General Assembly should address them when drawing districts this year. The legislature should also consider long-term redistricting reforms.

The North Carolina Supreme Court Gets It Right on Redistricting

The North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed in Harper v. Hall that claims of partisan gerrymandering are “nonjusticiable, political questions.” Whatever you may think about the political consequences of redistricting in North Carolina, not everything you dislike is unconstitutional.

Our state constitution has few but clearly spelled-out restrictions on the General Assembly when it draws state legislative maps. The maps must be roughly equal in population. They must be contiguous. They must keep traversals of county lines as few as possible (Article 2, sections 3 and 5 of the North Carolina State Constitution, as interpreted by the court in Stephenson v. Bartlett). Achieving a particular partisan balance is nowhere to be found in the constitution — which is also true for congressional maps.

Faced with that reality, the former Supreme Court majority misapplied parts of the constitution that protect individual rights (such as the Free Elections and Free Speech clauses) to make up a collective right for the minority Democratic Party to win a minimum number of state legislative and congressional seats. It was a right the court had never discovered in the century-plus the Democrats were in the majority.

Ironically, the outgoing lame-duck Democratic majority on the court paved the way for the correction. They bypassed standard judicial procedure in order to hear Harper v. Hall early and issue a ruling in December (“Harper II”). That last-minute decision paved the way for General Assembly defendants to petition the court to rehear the case through another little-used procedure, resulting in the “Harper III” decision on April 28.

The Harper III ruling did not overturn any precedent. It was the final decision in Harper v Hall. It is as if the Harper I decision never existed. Lawsuits over claims of partisan gerrymandering may now be behind us, at least for a while.

What the General Assembly Should Do about Redistricting This Year

The state Supreme Court not only overturned the maps drawn under Harper I last year, it also overturned the original maps the General Assembly drew in 2021. The opinion said that the General Assembly drew those maps under a “mistaken interpretation of our constitution” imposed by an earlier court decision and so the maps were “not constitutionally ‘established.’”

For those reasons, the Supreme Court order in Harper III requires the legislature to redraw all state legislative and congressional maps this year.

How should the General Assembly draw those maps?

They must follow the constitutionally mandated requirements (roughly equal in population, contiguous, and as few county-line traversals as possible for state legislative districts). In addition, the districts should be as compact as practical while keeping with the constitutional requirements.

In addition, the General Assembly should not use partisan data, such as voter registrations, election results, or racial data. They should also minimize splitting precincts and municipalities.

Those happen to be criteria laid out by the legislature in 2021.

What should we expect from maps drawn under such a process?

From data introduced during the 2021 redistricting process and subsequent litigation, we know the most likely partisan balances of maps drawn using politically neutral criteria. They are:

- State House: from 69-51 to 67-53 Republican

- State Senate: from 29-21 to 27-23 Republican

- Congress: 9-5 or 8-6 Republican

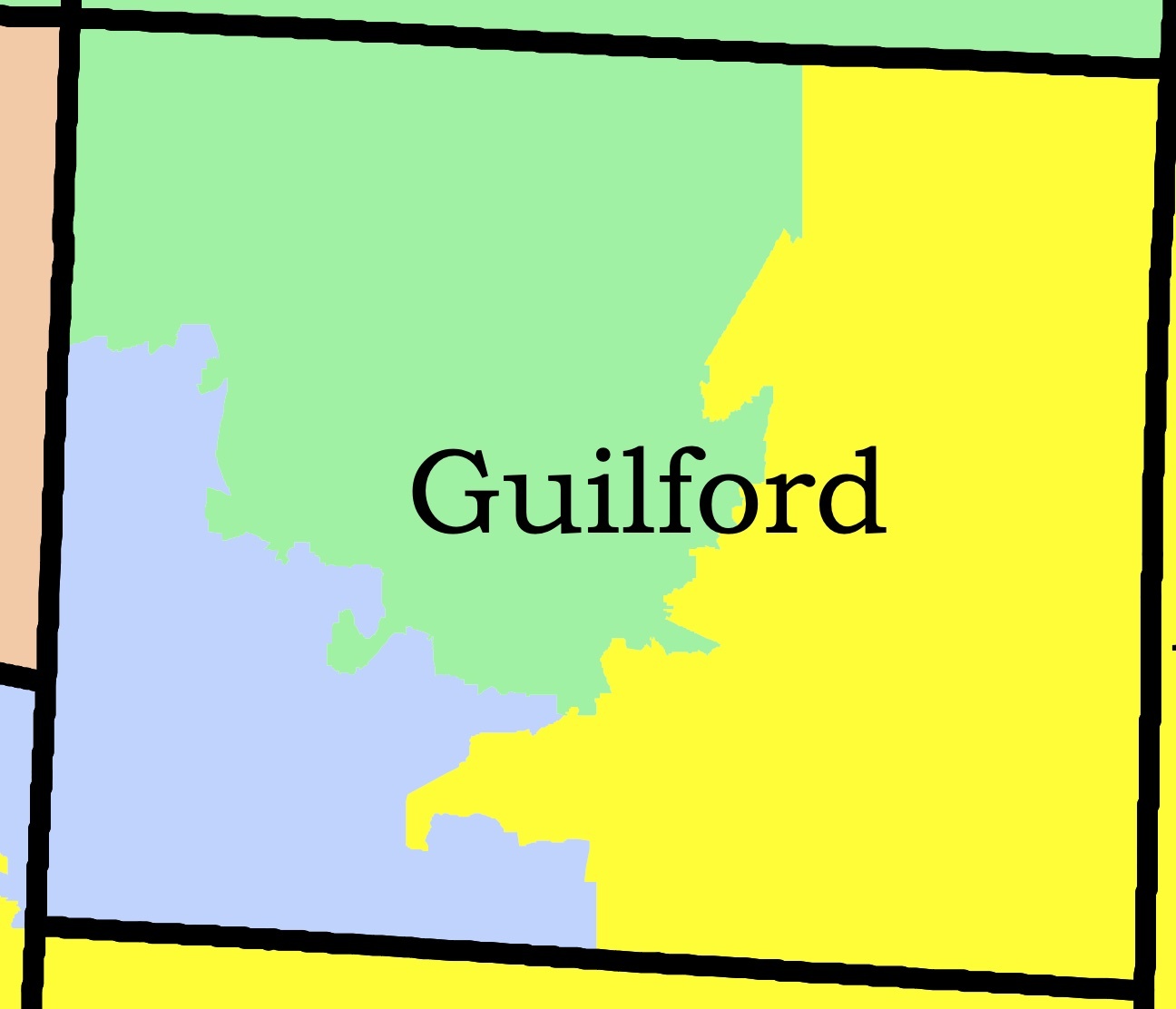

Those were not, however, what the General Assembly produced in 2021. While the 29-21 Senate map was within the normal range, the 10-4 congressional and 70-50 House maps were more favorable to Republicans than expected when using politically neutral criteria. Those unlikely outcomes, combined with some odd mapping choices (such as a gratuitous three-way split of Guilford County in the congressional map), suggest that the General Assembly can do a better job of more strictly applying those standards this time around.

Detail of the congressional map drawn by the General Assembly in 2021 showing Guilford County split between three districts. Source: North Carolina General Assembly

Now without the threat of a partisan gerrymandering lawsuit, legislators should implement the 2021 criteria again. Only this time they should do so voluntarily and more strictly. Maps so drawn would have fewer split precincts and more compact districts than the 2021 maps. They would also not have problems such as the three-way split of Guilford County in the 2021 congressional map.

Time to Consider Long-Term Redistricting Reforms

Once they complete the maps to be used for the remainder of this decade, legislators should consider redistricting reforms for maps drawn after the 2030 census.

We had no shortage of reform proposals in 2019, ahead of the 2020 census. Two of those bills, House Bill 69 (Nonpartisan Redistricting Commission) and House Bill 140 (The FAIR Act) had the most promising reforms. Redistricting reform should take elements of both bills, including:

- Incorporating the county grouping system devised in Stephenson v. Bartlett into the North Carolina State Constitution

- Banning the use of partisan and racial data by constitutional amendment

- Requiring districts to be as compact as practicable by amendment or statute

- Prohibiting consideration of incumbents’ home addresses

- Mandating transparency in the process

A reform package could also include a bipartisan advisory redistricting commission to create draft maps. As proposed in HB 69, the first two sets of maps drawn by the commission would be voted on by the General Assembly but not subject to amendment. A third set would be subject to amendments.

Legislators should implement those reforms in the 2024 or 2025 sessions, well before the next round of redistricting. Neither party knows how shifting partisan preferences will affect election outcomes several cycles into the future. While Republicans currently enjoy a geographic election advantage in North Carolina, that could change if Democrats succeed in winning over suburban areas. Such a change would put Republicans in the same position as Canada’s Conservative Party, which is relegated to the opposition despite winning the most votes in the past two parliamentary elections.

It is also worth remembering that Republicans first gained their current majority in the 2010 election by winning in maps that Democrats drew for their own advantage.

Such uncertainty may help ease the way for redistricting reform.

With partisan redistricting lawsuits likely a thing of the past for the near term, now is a good time for reforms.