Burr: A chill running through the GOP

Published February 18, 2021

Three-term U.S. Sen. Richard Burr was one of seven Republican senators to vote for the conviction of Donald Trump at the ex-president’s second impeachment trial. For that, Burr joined another club: The Censured GOP Senators.

As I write this, Burr and colleague Bill Cassidy of Louisiana have been censured by their state parties for the guilty vote. Sen. Ben Sasse of Nebraska may become a member any day now. Maine Republicans are trying to decide whether to rebuke Susan Collins, as is the Pennsylvania GOP with Pat Toomey.

A censure resolution is circulating across Alaska targeting Sen. Lisa Murkowski, the only senator voting to convict who’s standing for re-election in 2022. My guess is she’s not too concerned, since in 2010 she won her second term as a write-in candidate, beating a Republican, a Democrat, and a Libertarian.

Sasse had some tough love(?) for his party:

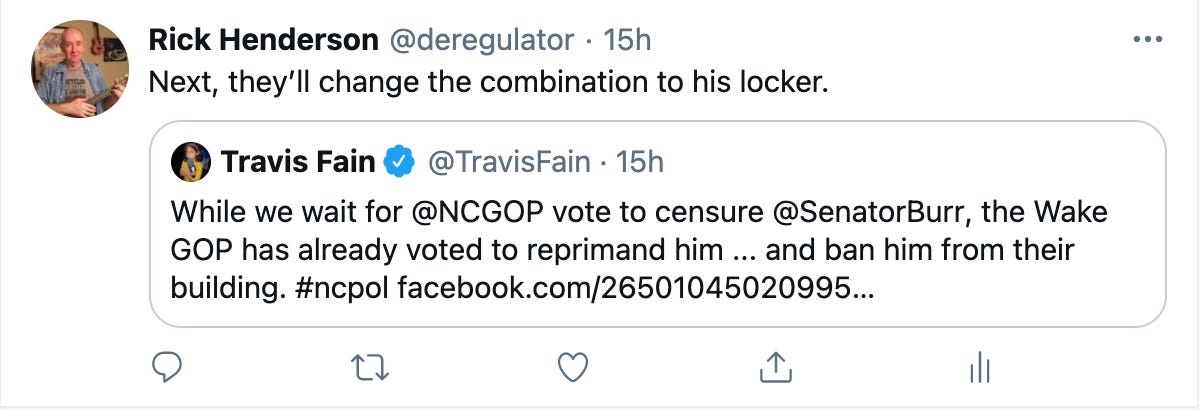

Burr may be more disappointed than anything from Republicans’ actions, which in one instance bordered on juvenile. The Wake County Republican County both censured Burr and banished him from county GOP headquarters.

This led me to quip on Twitter:

Beyond the comedy and perhaps sadness of it all lurk a fundamental disruption of what political parties are supposed to do: “getting candidates who can actually win in November.”

That’s what Republican Senate Leader Mitch McConnell told the Wall Street Journal after he voted to acquit Trump. McConnell is right. Political parties aren’t supposed to gratify the egos of individuals or harbor “loony lies and conspiracy theories,” as the Kentucky senator said of Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene.

In our first-past-the-post, winner-take-all system, well-functioning political parties are designed to build coalitions, preferably around a broad set of principles, and win elections.

But parties are malfunctioning. The candidate who can grab the most attention and cause the most outrage can shove aside the low-key contender who takes problem-solving seriously.

University of Massachusetts political science Raymond J. La Raja described the value of healthy parties in 2015:

“Political parties play a vital role in democratic politics by guiding voter choices, aggregating interests, and holding politicians accountable through meaningful partisan labels.”

Because they care most about winning, “party operatives tend to channel financial support to relatively moderate [I’d say electable] candidates for Congress and state legislatures.”

Committees also “serve as financial mediators, a buffer between ideological donors and candidates. In a political system where money flows significantly through parties, these committees raise money from ideologically oriented contributors and reinvest the funds in a wide array of candidates, including many moderates.”

La Raja may not have seen the rise of a candidate like Donald Trump, driven more by personality and grievance than any concept of governing, but La Raja’s analysis helps explain how an outsider with no partisan loyalty can swoop in, take over a party apparatus, and use it to support his own agenda.

The parties control donor lists, ballot access, media credibility, and an entire infrastructure geared around elections. It’s why third parties have failed to gain lasting traction in the U.S. The cost of booting up a new party from scratch is prohibitive. Then you have to finance candidates and campaigns. It’s much easier to snatch an existing party that’s ripe for the taking.

The 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign law made the fall of parties possible, La Raja says. By banning large individual contributions to parties and campaign committees, money could bypass parties and go straight to PACs and other independent spending groups that face no contribution limits. Parties and campaign committees — which directly seek to influence power — also face more financial scrutiny than outside groups, as they should.

La Raja sees McCain-Feingold as an accelerant to the trend of parties nominating “people on the extremes.”

Maybe. Rather than ideological extremists, though, as parties have withered, we’ve seen the rise of the celebrity candidate with little governing experience — Jesse Ventura, Arnold Schwarzenegger … and Barack Obama. Obama rejected public financing for his 2008 general election campaign. He, and the groups backing him, could spend at will. It worked — and it established a template for the campaigns that followed.

Obama-allied but ostensibly independent groups pummeled John McCain in ways a party-run committee couldn’t.

But them’s the rules, which Obama used to his advantage, and occasionally violated.

Trump ran around the GOP like no nominee before him, largely due to the media’s obsession with The Donald — he got nearly $6 billion in free mediaduring the 2016 cycle, according to one watchdog group. His campaign spent less than $400 million.

Trump’s ability to leverage the airwaves has inspired a new wave of candidates I called the Green Room Caucus — political actors more interested in appearing on talk radio or cable gab shows than in promoting policies or governing.

It’s not a partisan phenomenon, even after Obama has left the stage. In 2018 and 2019, Democrats brought us The Squad. Bernie Sanders, in his own rumpled way, captivated left-leaning viewers.

Joe Biden won. He cut through the clutter largely by staying off social media.

I see no quick fixes. La Raja says dramatically boosting the amount of money individuals could give parties — perhaps with taxpayer financing — would let parties compete more with outside groups.

Perhaps. But both major parties appear hellbent on promoting show horses over work horses. Pretty faces and loud voices over people of substance. People who want to “own” the other side rather than work with it. Biden could be, as he said, a transitional candidate. The last president who tries, at least in style, to appeal to those who disagree with him.

After that, no one knows. Winning elections is a matter of getting one more vote than the other side. The GOP is leading with its chin, ignoring basic math. Though don’t count out, pun intended, the Democrats’ ability to follow along.

As for North Carolina, candidates are jockeying to succeed Burr, who’s retiring next year. On the Republican side, former U.S. Rep. Mark Walker is in the race; former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and current U.S. Rep. Ted Budd may join. They’re all vying to prove who’s the Trumpiest.

But why not the real thing? The 45th president’s daughter-in-law, Wilmington native Lara Trump, is all the rage in some GOP circles. Trump’s biggest buddy on Capitol Hill, S.C. Sen. Lindsey Graham, seems to be acting as Ms. Trump’s informal campaign manager.

If she chooses to run, she’ll have to move here from New York City.